Why is Russia scared of the European Union?

For centuries, Europe has been a symbol of the fragmentation of nations and countries, intense rivalry, and the source of both world wars. But it also became an experimental laboratory, where the European Union, a unique political system, was created. Ukraine has recognized this system as a desirable and comfortable environment, consistently pursuing own course toward European integration.

Russia was initially interested in allied relations with the new Europe, but in the years since the onset of Putin's rule, it has made a dramatic shift. To explain this metamorphosis, the "theory of humiliation" was invented. They claim Europe has allegedly offended Russia and pushed it away. In fact, the reason was quite different.

Uniting for peace

The dream of a united Europe is centuries old. Although it was Western European nations who originally came up with it, the dream was shared and pursued throughout the continent.

Among the first to try to translate it into a practical plane was the Slavic monarch — George of Poděbrady, King of Bohemia from 1458 (and the Czech King from 1469) to 1471. He put forward a radical proposal that can be considered the original model of the EU: he proposed a treaty between all Christian states, including Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, Bavaria, and France, to resolve all differences by peaceful means to end all fighting. The union implied a joint parliament and other common institutions.

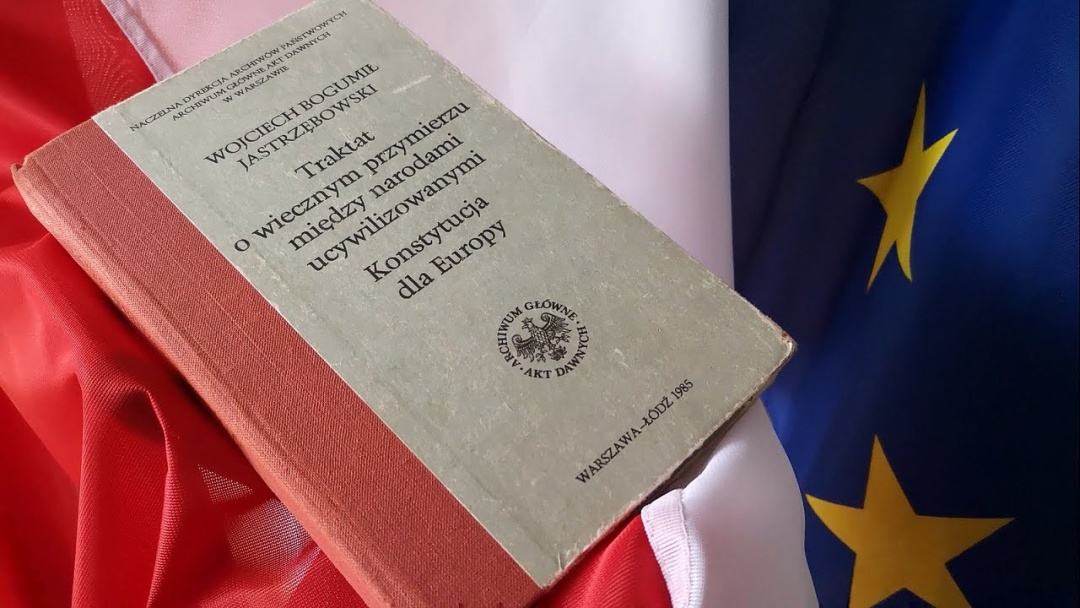

Although his idea was never meant to be realized, it prevailed. From time to time, projects to unite Europe have been suggested by philosophers, public figures, and politicians. Later, in 1831, Polish scholar Wojciech Jastszembowski formulated a document entitled "On Eternal Peace among Nations" ("O wiecznym pokoju między narodami"). In essence, it was a draft of the first constitution of Europe, united as one republic without internal borders, with a single judiciary and institutions composed of representatives of all nations.

In early 20th century, the idea of creating the "United States of Europe" was actively promoted by Tomas Harrig Masaryk, the first president of Czechoslovakia.

Mykhailo Hrushevskyi also dreamed of a European federation, of which Ukraine should become a part, one of the "strongest, toughest, and most certain".

After two world wars and against the background of the Soviet threat, Europeans finally began to realize their centuries-old dream with the active support of the United States.

But the Treaty establishing the European Union, also known as the Maastricht Treaty, was signed only on February 7, 1992. Its ratification brought the European community to the level of political integration.

"For our freedom"

Back in 1993, the Ukrainian government declared integration into the EU a foreign policy goal. This desire was natural, as Ukraine belonged to the European civilizational space. It’s been connected with Europe geographically, historically, and culturally. And — probably, most importantly — by the type of its political system.

Historian Yaroslav Hrytsak noted that the key argument in support of this thesis was formed by Ukrainian liberal historiography in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In particular, he refers to the words of politician Viacheslav Lypynskyi: “The main difference between Ukraine and Moscovia is neither the language, nor the tribe, nor the faith, but a different political system forged through centuries, a different... method to organize the governing class, a different distribution of the wealthy and the poor, the government and the citizenry.”

To a large extent, Hrytsak continues, the developments seen after the fall of communism confirmed this assumption. He mentions an article by Russian historian Dmitri Furman entitled "Ukraine and Us" (1994). He wrote that the first years after the fall of Communism showed how sharply Russia and Ukraine diverged in their political trajectories. There was a deep political crisis in both countries. But in Russia, it ended with the president deploying tanks to open fire at the Parliament HQ in 1993. In Ukraine, on the other hand, the political struggle between Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma ended with the former peacefully handing over power to the latter. Ukrainians, Furman concluded, passed the exam for democracy, which the Russians failed, and it remains unclear, when they will be able to pass it.

However, in late 2013 and early 2014, Ukrainians had to fight for their right to be part of Europe at the cost of their own lives. To live based on freedom, democracy, rule of law, and human dignity. They still have to defend their choice in the ongoing war with Russia, the neighbor that seeks to divide Europe and assert own dominance.

While “European values” are a fairly recent concept, they are based on old traditions, adds Hrytsak. “This is about the fundamental feature of modern Europe — democracy. The European democratic tradition dates back to ancient times. It meant certain very practical benefits. Herodotus was already trying to explain how a small tribe of Greeks could defeat a huge Persian power — and he interpreted the Greco-Persian war as confrontation between the West and East. His explanation was simple and convincing: the Persians and other tribes fought under the coercion of a despot, while the Greeks fought as free people. This same idea was repeated by Pericles in his speech at the vigil for the fallen Athenians: we live free in our country, and for our freedom we are ready to fight fearlessly and die on the battlefield,” says Hrytsak.

Thus, the words of the Ukrainian anthem echo the words of the thinkers of Ancient Greece, the cradle of European democracy.

Speaking of a modernized and motivated Ukrainian Army, France24 compares it to the biblical David, a young shepherd who defeated the giant Goliath despite seemingly unequal forces. Because he fought for the freedom of his people.

Russia integrating with Europe

The above-mentioned Masaryk and Hrushevskyi (at least at some stage) believed that Russia should be part of a united Europe. Many Russian and Western experts believed in the 1990s that Russia would integrate into European structures. Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyriev dreamed of Russia's membership in the EU, and British Prime Minister John Major called for "expanding the imagination" and inviting Russia there. The EU-Russia Cooperation and Partnership Agreement was signed in 1994 and entered into force on 1 December 1997.

Even Putin in the first years of his administration did not rule out future integration with the EU. "We intend to work towards the unification of our legislation with the European one and do not intend to reduce our ties with Europe, but, on the contrary, we intend to expand our cooperation in all areas. I want to emphasize this — in all areas. And I do not rule out the possibility that at some stage in our relations between a united Europe and Russia, integration-related issues will come up on the agenda,” he said in an interview with French TV channels in October 2000.

In addition, he stressed that EU enlargement “did not cause any fears" in Russia, moreover, it "welcomed" this process.

...but

But as soon as 2004-2005, the conflict between Russia and Europe flared up over the presidential election in Ukraine. Putin categorically denied letting Ukraine get any closer to Europe.

Some Western politicians and experts believe it was an "insult" the West allegedly inflicted on Russia by moving into the territory of Moscow’s supposedly legitimate interests that was a major reason for the deterioration of relations between Russia and the West. Perhaps this is what Emmanuel Macron meant when he spoke about the need to understand the "modern traumas of this great nation” (Russians — ed.).

However, such an interpretation is offensive primarily to Ukraine. But it’s not the only thing. If Russia had adhered to the declared course of European integration, how could Ukraine's European integration "offend" it?

The reason is evidently something else.

In 2010, at a conference in Germany, then-Prime Minister Putin asserted his confidence that Russia would one day join the Eurozone. And this was against the backdrop of the raging crisis of that time!

Over the years, Russian propaganda simultaneously denigrated the EU, predicting its imminent demise and promoted the hypothetical idea of a “Great Europe” (“from Lisbon to Vladivostok”). They claimed that Russia's accession to the European Union would give it new strength. The Europe Plus Russia alliance could become a true world superpower, the only power in the world capable of competing with the United States. Russia was actively promoting this idea through its "proxies" across Europe.

The Kremlin made every effort to get the UK to withdraw from the European Union. It did nothing to hide its joy when this finally happened. The pro-Russian Croatian newspaper Advance, among others, wrote that Russia could take the vacant seat.

This may be indeed in line with the Kremlin's secret dream. This may also be a useful lens to look at the statement made just a week ago by Putin’s press secretary Peskov: “The Anglo-Saxons, of course, are really boosting tensions on the European continent. That’s something for us, Europeans, to think about... And until we, Europeans, realize that it hurts us all, I don't think we can fix it.”

That is, Russia still does not seem to mind taking its place in Europe. But it does not want to be an equal among equals; it wants to dominate. Not only in Europe but also in the world. In scientific terms, this was called “proportional representation at the European table” and “historic British-Russian rivalry for world domination.” Criticizing the united Europe, Russia frequently claims that its father was allegedly Hitler (who, in turn, was an “Anglo-American invention,” of course).

In addition to the fact that the idea of a united Europe is hundreds of years older than Hitler, he did not "unite" but conquered it, creating the complete opposite of what Europeans dreamed of: a centralized empire with a dominant ethnic group for which Europe was only necessary “living space.” He started it with “protecting” Germans, the keepers of great culture and language, who allegedly suffered in Czechia and Poland because they had to study some “inferior” languages.

If we recall his well-known envy of the Anglo-Saxons, mixed with hatred, contempt for the Americans as a "rootless" nation incapable of high culture, and respect for their economic power at the same time, the resulting image seems almost identical to that of the "Russian world."

Back in 2004, Eurozine noted that in Russian political discourse, there is a certain opposition of Europe and the West (USA, NATO), where the West is portrayed as a destructive entity of sorts which is constantly trying to undermine the balance in Europe, while Europe is a passive, suffering entity, an arena of political and military struggle. It is deprived of its own agency, the only question is who will govern it.

According to Vladislav Surkov, a long-time apologist and grey cardinal of the Kremlin, “Russia will get its share in the new global gathering of land (or rather space), confirming its status of one of the few globalizers, as it happened in the times of the Third Rome or the Third International. Russia will expand not because it is good, but because this is physics.”

The original version of absolute values

What really happened in the above-mentioned period between 2000 and 2004, if no one "insulted" Russia?

As oil prices continued to climb, Russia's political elite was becoming more confident. The nuclear factor was now strengthened by the component of raw materials. This allowed Russia to get a sense of its own grandeur and self-sufficiency. It was then that the Russian political class turned back to authoritarianism and the old great-power ideology, that is, the form of personalist power that is natural and familiar to Russia.

The infamous arrogant question, "Who are you to f***ing lecture me?” in the spirit of new Russian diplomacy, was addressed by the Russian Foreign Minister to the British Foreign Secretary later, in 2008. This was the first statement, but far from the first thought. Shortly after Putin came to power in Russia, the attitude was that Russia had nothing to learn from the West, if anything, the West was supposed to learn from it instead.

This was phrased in a more civilized manner by political technologist Gleb Pavlovsky in 2004, in his foreword to the book Russia without Europe: “Today, we see a rigid official — an interpreter of ideals teaching Euro-Atlantic values to inferior easterners (did Anton Chekhov know about them?)... Nations are invited to adopt a standardized package of values together with the authority that has the right to control them ... Russia defines itself as a European state, which is at the same time a civilization — the bearer of its own version of absolute values.”

Here again, Hitler was called the founder of the European Union, and Russia — a freedom-loving anti-fascist country that opposes "totalitarian unification." The text also stated that Russia would not allow the unification of its part of Europe. What this meant was clearly not the European part of Russia, since the entire book is dedicated to the idea that Russia was allegedly left behind by Europe. In this veiled manner, Russia defined the sphere of its supposedly legitimate interests.

Russia “rose from its knees” and got the taste of sovereignty, which it understood as the mandate to do whatever it wanted. The political (“network”) structure of the European Union scared it, and even more so — the “growing impact of the international humanitarian law and human rights, which restrict the power of state leaders over the citizens of their countries.”

Simply put, the Russian political class was concerned that the people could no longer be considered serfs, and that power in general was losing its clear outlines.

Anton Chekhov, anti-fascism, and the "theory of humiliation" masked the trivial turn to authoritarianism in domestic policy and aggression in the foreign arena.

The three wise monkeys

Even though Ukraine had proved its desire to join the EU years ago, it had to break loose off the claws of a fraternal "embrace," kicking and screaming its way out. Of course, Russia's policy is not the only reason why Ukraine has still not become a European Union member. But it has always been the main reason. Before Russia resorted to outright aggression, it had created more covert obstacles — blackmailing, manipulating, and corrupting Ukraine - and lying that it was Russia that was being "insulted" and "humiliated."

Former Danish Foreign Minister Uffe Ellemann-Jensen answered a question about the West and Russia the following way: "I do not support the popular idea that the West failed to help Russia in the 1990s. Let me remind you that the West provided great assistance to Russia. But in Russia itself, there were no conditions for a new ‘Marshall Plan’. I also do not accept the ‘theory of humiliation’ of Russia from the West because the enlargement of the EU and NATO was part of the raison d’etre of these organizations, and this enlargement did not pose any threat to Russia. I am convinced that the West lost just when its political leaders ceased to be honest in their relations with Russia. For various reasons, they were silent when Russia rolled back from democracy, and they looked on when Russia violated the principles approved by the OSCE and other international institutions. I'm not saying that Western leaders should have isolated Russia. On the contrary, they had to raise their voices when Russian leaders renounced their commitment to freedoms, human rights and relations with independent states. Apparently, the West adopted the position of the famous three monkeys: see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. I doubt that such a position of the West can encourage the leaders who have had a taste of authoritarianism to respect Western values...”

Center for Strategic Communication and Information Security