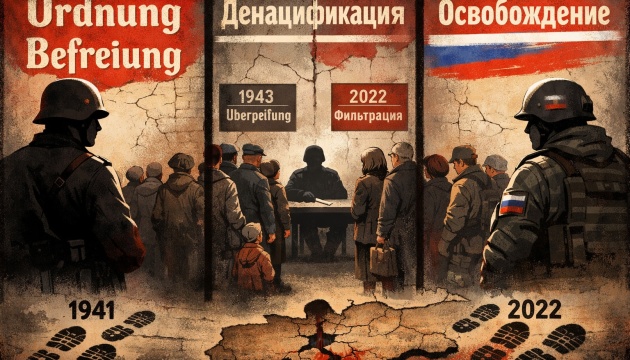

How Nazi and Contemporary Russian Ideologies Dehumanize Ukrainians

Russian media outlets are now openly showcasing images from Ukrainian cities—including, and especially, Kyiv—which have recently been suffering from large-scale Russian strikes on energy infrastructure.

In this context, well-known Ukrainian journalist Denys Kazanskyi has made a pointed observation. He notes that Russians who have built their identity around the myth of the “Great Patriotic War,” and who regard the Siege of Leningrad as one of its greatest tragedies, are now effectively doing the same thing to Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities—forcing civilians to endure cold and deprivation, while expressing satisfaction that some shops are running out of bread.

“All of them grew up hearing that the Siege of Leningrad was one of the greatest crimes of the twentieth century—about how the Nazis acted with extreme inhumanity. Unable to capture the city, they took revenge on civilians through cold, hunger, and slow death. And now—this very same thing—they are doing to Ukrainians. With only one difference: the Germans never called Russians a ‘brotherly people,’ whereas today’s Russia is obliterating those whom it had itself called brothers for decades. A devotee of Stalin and the USSR, Russian war blogger Maksym Kalashnikov cynically reflects on how his state, under the slogan of ‘denazification,’ is reproducing the very tactics used by the Nazis during the siege of Leningrad.

“I do not know what kind of mutations had to occur in these people for them to become what they are. But what we are witnessing is one of the clearest and most disturbing examples of moral degradation and brutality in world history,” Kazanskyi concludes.

Moscow’s “Denazification” Logic

In fact, this brutality has a very concrete ideological foundation. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ journal Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn (‘International Life’) published an article suggesting the application of the Soviet experience of occupying Germany after the Second World War to achieve what it calls “one of the key objectives of the Special Military Operation— the denazification of Ukraine.” The very appearance of such idea in an official publication whose editorial board is chaired by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov indicates the institutionalization of an occupation-based logic within Russia’s official discourse.

In the introductory note, the author, identified as Grachova, refers to Vladimir Putin’s address of February 24, 2022, in which he “defined the denazification of Ukraine as one of the most important goals of the special military operation.” To achieve this goal, she argues, it is essential to draw on the “rich practical experience” accumulated by the Soviet authorities “while addressing a similar task in the territory of the German zone occupied by the Red Army as a result of the Second World War.”

Grachova claims that the Soviet authorities began acquiring experience in “denazification” already at the final stage of the war, including through the activities of the NKVD at the front. She also describes the work of the Soviet Military Administration established to govern the Soviet occupation zone in Germany. Particular attention is devoted to the activities of so-called “denazification committees.” According to the author, by 1948 these bodies had “removed” approximately 520,000 “former members of the Nazi Party, militarists, and war criminals” from local self-government bodies and businesses.

According to the article, by 1948, the military administration had “carried out the key democratic transformations in Eastern Germany, purged local self-government bodies, the police, and the judiciary of overt and covert Nazis, and formed regional and provincial governments,” to which it subsequently transferred full authority.

“The experience accumulated by the Soviet occupying authorities in the denazification of Germany should be used by Russian state and military authorities when carrying out similar work in territories ‘liberated’ during the ‘special military operation’ from the power of the so-called Kyiv neo-Nazi regime. Unfortunately, at present this experience is being applied on a limited scale,” Grachova concludes.

What is being proposed, therefore, is the legitimization of long-term occupation, administrative control, and repressive practices, disguised as a historical analogy. The article published by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs demonstrates that the concept of “denazification” in Russia’s official discourse has lost any connection to actual history or international law and has instead become a universal ideological instrument used to justify war, occupation, and the coercive transformation of seized territories.

Russia Replicates Occupation Practices of the Second World War

Equally revealing are the parallels between the German occupation of Ukraine in 1941–1944 and the current Russian occupation—above all in terms of the denial of Ukrainian statehood and political subjectivity. The Third Reich did not regard Ukraine as a state. The territory was treated as Lebensraum and as an administrative space for the Reich. Any manifestations of Ukrainian statehood or political autonomy were eliminated. In the contemporary Russian version, Ukraine is likewise denied recognition as a full-fledged state and nation. In official Russian rhetoric, Ukraine is presented as an “artificial construct,” “part of Russia,” or a “historical mistake.”

During the German occupation, Ukrainians were classified as Untermenschen—a labor resource without political rights. The population was divided into those deemed “useful” and those considered “expendable.” In the Russian narrative, Ukrainians are labeled as “Nazis,” “infected,” “zombies,” or “biomass” that must be “cleansed” or “re-educated.” In both cases—then and now—this constitutes explicit dehumanization, serving as a precondition for the perceived permissibility of mass violence.

During the German occupation, the rhetoric of “liberation” was framed as “liberation from Bolshevism” and from the so-called “Jewish yoke.” The Russian narrative is framed as “liberation from Nazism” and the “protection of Russian speakers.” In both cases, invasion is presented as a supposed “moral mission.”

Both the Nazis and the contemporary Russian regime use terror as an instrument of governance. The Nazi occupiers carried out mass executions, punitive operations, village burnings, and established concentration camps. Russian forces organize filtration camps, employ torture, and commit mass killings of civilians, as seen in Bucha, Izium, and Mariupol. In both cases, fear and violence function as the core mechanisms of control.

The economic exploitation of Ukraine by both regimes is also comparable: the theft of grain, metal, and labor. In the Russian case, this has been supplemented by forced “passportization,” alongside mobilization into the Russian armed forces, as a tool of economic and administrative control.

During the German occupation, there was a deliberate targeting of the intelligentsia, clergy, and national activists. Under Russian occupation, there are arrests of mayors, journalists, volunteers, and school teachers. In both cases, the occupying regimes have deliberately struck at the social “nerves” of society.

The Nazis forcibly deported children for forced labor and implemented Germanization of those deemed “suitable.” Russian authorities have carried out large-scale deportations of Ukrainian children and introduced programs of so-called “re-education” and ideological indoctrination.

Thus, both the Nazi and the contemporary Russian occupations of Ukraine are based on the same underlying logic: the denial of the right to exist, dehumanization, terror, genocide (including attacks on energy infrastructure), and attempts to break national identity. The difference lies only in the invented ideological frameworks—today articulated by Russia’s Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn—used to disguise these practices.

Max Meltzer